A map of Scandinavia will show that the Baltic Sea has a very long, finger-like extension that separates Sweden from Finland. The whole of it is referred to as the Gulf of Bothnia but its areal extent is so great that it rivals that of the Baltic Sea’s main body farther south. Today we’re beginning the 400-500 mile trek down the Swedish side of the Gulf, a transit that we will do over the course of three days with stays in the small coastal cities of Umea, Sundsvall, and Gavle. By mid-afternoon Popeye and I reach Umea, the first of them.

Our lodging in Umea is at the Hotell Gamla Fangelset, only a few blocks removed from the city center. This is an historical building that dates back to the 1860’s — not very old by European standards The town of Umea has been around since the 14th century but most of it was consumed by fire in the late 1800’s. Gamla Fangelset was one of the very few buildings to survive the fire.

Because of the fire, Umea has physical attributes not terribly different from what one might find in Canada or the US: broad streets sheltered by shade trees, residences suggesting middle-class prosperity with little to suggest opulence, city parks of ample dimension, and a goodly collection of post-War buildings to indicate recent growth. One major difference, however, is that here we have the classically European central plaza with a downtown core that to the maximum degree possible is made out-of-bounds for vehicular traffic. It is an engaging city, more lively than usual for its small size but also unhurried in its pursuit of work and play.

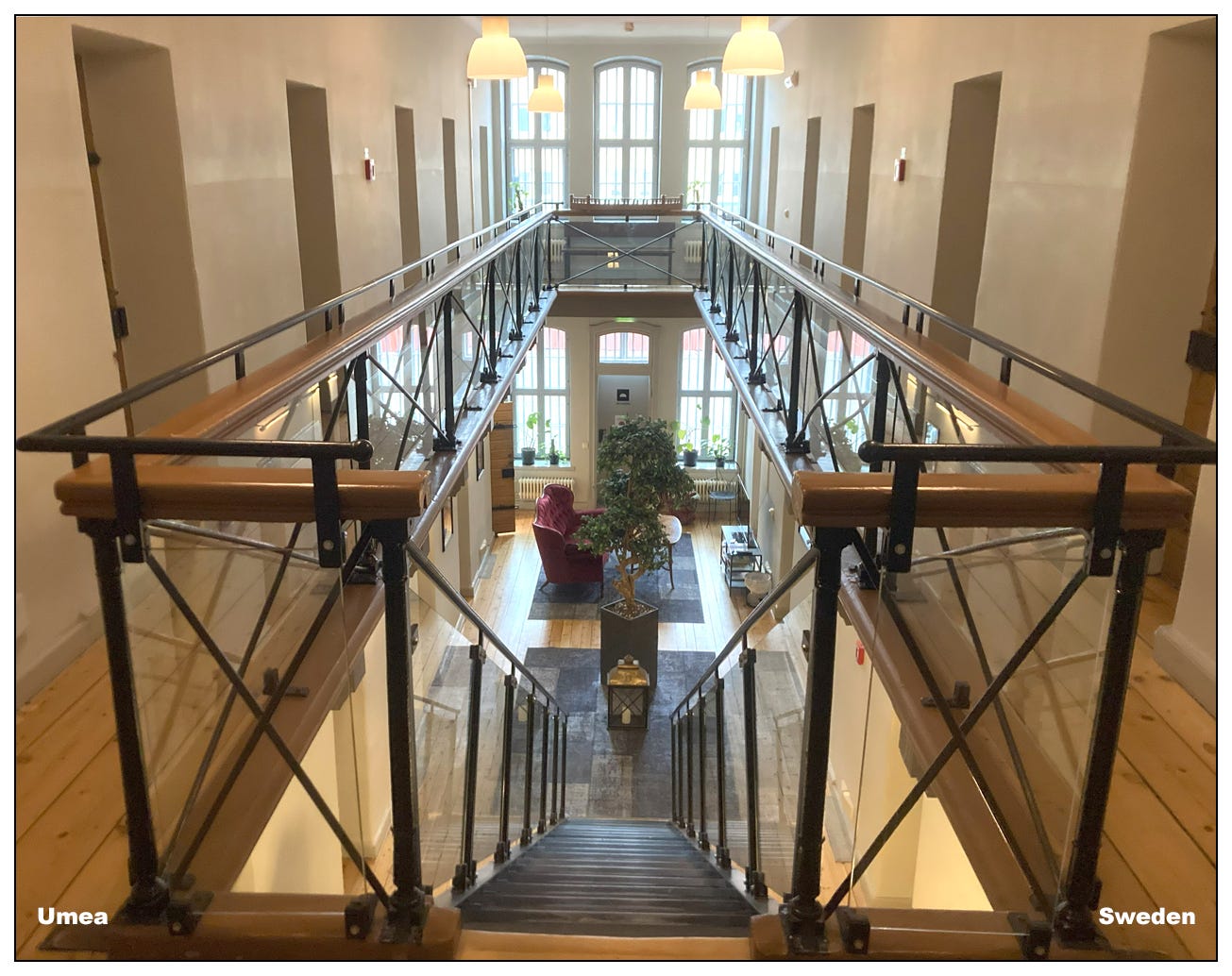

The Hotell Gamla Fangelset was built as a prison. It functioned as such up until the 1980’s when it was abandoned and left to deteriorate. More recently, government got involved in restoration and oversaw the make-over from prison to lodge. It is now an historical landmark.

Staying here is a relative bargain because of the single beds, small room sizes, and shared bathrooms. There are a few other converted prisons in Scandinavia that cater to travelers, and I do recall staying in one in southern Finland when Popeye and I passed through in September of 2021.

Gamla Fangelset was constructed to effectuate a new way of making convicts into respectable citizens -- a philosophy borrowed from a progressive vision recently implemented in the United States. Up until then, it was common practice in Europe to throw all inmates into a giant dungeon where all the miscreants suffer in each other’s company, but Philadelphia (PA) latched onto the notion that convicts should be cured of their criminal behavior and not just punished for their misdeeds. The idea was to isolate the prisoners by putting each one in a separate cell, thereby creating a proper environment for self-reflection. It was thought that silence and solitude might induce the level of introspection needed for a convict to recognize the error of his ways. It seems the thinking was that what had worked for monks might do wonders for criminals.

Nowadays, the idea of individual cells is less popular. In fact, we think of them as a form of solitary confinement and generally deplore the practice as cruel and unusual punishment. Not having had experience with prison life, anything I say is hardly more than idle speculation, but what is demonstrably the case is that whatever philosophy is being pursued at present is not working very well. The rates of recidivism are high and repeat offenders clog the prisons.

And it is not really clear what philosophy is being pursued anyway. Prisons in the United States do seem to be committed to the idea of a cell for each prisoner, but have had to adjust to a growing prison population by double bunking -- and that of course violates the rationale used to construct cells in the first place.

Getting back to Gamla Fangelset as a prison, the morays from the 1800’s were such that even prisons were designed with respect for a touch of elegance. Doorways, iron bars at the small windows, second floor railings along the catwalks -- things like these were treated with something more edifying than brutal functionality. Attention to detail and concern with aesthetics must have been more highly valued in those old days. Of course now as a hotel a great deal of energy has been spent on making things nice for the customer, but no amount of superficial ornamentation can make a deformed structure look friendly. The interior of Gamla Fangelset is an inviting space and the stark, narrow cells are cosy nests.

Major streets in Umea are lined with mature birch trees. I’ve seen quite a bit of birch here in the Scandinavian north but they are different from those of my youth in upper New England. There, the birches are slim and flexible; here in Scandinavia they are stout and stand erect. There, the color of the trunk is a creamy white whereas here the trunks carry a hint of gray. There, the horizontal streaks in the bark are subtle slivers that look like darkened leather whereas here the streaks are more like open wounds oozing black blood. Every tree must go through the natural aging process, but I visualize New England birches as joyful adolescents and the birches hereabouts as venerable graybeards.

Kristian, the manager of Gamla Fangelset, suggests I might be interested in visiting the Guitar Museum located right next to the bus terminal in the center of Umea. Kristian is a congenial fellow, an unflappable, sandy-haired Swede whose ample height and big-boned body make his glasses look ridiculous. They are small circular lenses set in a black plastic frame and are too small given his head size and overall bulk. I groused at him when we first met because when I arrived at Gamla Fangelset there was nobody to let me in and rain was threatening. When at last Kristian showed up, I was grumpy but he responded with placid unconcern that somehow got me over my fit of pique. We ended up having extended conversations thereafter, but now in this instance, his suggestion doesn’t sound promising and instead I take a walk along the waterfront.

Umea is not coastal but does straddle an estuary of the Gulf of Bothnia that penetrates inland more than ten miles. The waterfront has a continuous walkway that extends to and perhaps beyond the two bridges crossing the estuary. The buildings lining it are connected to the city’s most important activity: education. Kristian claims that during the school year about 40,000 students move into town which makes Umea a pretty lively place. The school year recently ended, though, so I’m here during the quiet time.

In my wanderings, I do by chance pass by the guitar museum, and then on second thought return to take a look. I don’t know whether spending an hour gazing at guitars is proving to be worthwhile or not. Although I find it to be a tedious waste of time, I have to admit that my lack of interest is largely a function of extreme ignorance about music in general and the guitar in particular.

The museum is one long corridor around the perimeter of the top level in a large four-story commercial building. The looping corridor is lined on both sides with continuous displays of guitars. Some of the display cases also contain posters and paraphernalia associated with great guitarists, but most are filled with nothing but guitars. Overfilled, actually: guitars come at you like trees in a forest. To the undiscerning eye, they all look the same — like viewing a stamp collector’s albums in which each stamp is mounted stick-em side up.

The one distinction that even I manage to notice is the difference between acoustic and electric guitars. But even this categorization has its negativity: acoustic guitars are beautiful but lack individuality whereas electric guitars are ugly but at least have character. See what I mean when I say I’m no connoisseur of guitars?

Salvation arrives in the form of a sprightly young man with high-cropped hair and a birthmark on his left cheek. He is Michael Ahden, one of the two brothers who own the museum and he spends a half hour guiding me from display case to display case, pointing out who played this particular guitar or how rare and expensive that one is. Michael supplants my boredom with his enthusiasm.

What we have here is a world-class collection of guitars assembled by two brothers out of little more than obsessiveness. With little in the way of money, they collected guitars by choosing to buy them instead of other things. Now they have hundreds. For them to have overcome the obvious start-up costs associated with opening a museum that now pays for itself borders on the miraculous.

Part of the reason I find this museum to be so mystifying is that although I grew up in the ‘60’s (between ages 17 and 26), I never felt the magic of flower power, never became a hippie, never made it to Woodstock. I guess I was too old by then. Anyway, if like so many others of my generation I had succumbed to the hypnotic effect of the kaleidoscope I might better understand why a museum full of guitars has global appeal. Especially, I might add, electric guitars.

*****

Although the weather forecast dismisses the likelihood of rain during the ensuing two days, Popeye and I make our way south along the west side of the Gulf of Bothnia with occasional showers wetting us up pretty good. It doesn’t matter if they happen early in the daily passage since we get dried out after a couple hours of cruising down the highway. If it happens just before our stop for the night, though, shoes and socks and upper body layers of clothing have to be spread out to dry in my room for the night. That happens in Sundsvall, but Gavle we reach after the end of a spin dry cycle.

The two-day run south is a bit of a disappointment since I was hopeful we would often have the Gulf within view. But the highway is too far inland for that. The reason is occasional estuaries like the one in Umea. But on the plus side, the road is in good condition and the traffic is light. Roadside views are often limited by the all-encompassing forest, but every once in a while a picture window scene passes by.

This main highway — the E4 — has an unusual attribute: it is a spacious three-lanes wide but physically partitioned between one side that has a single lane and the other side which has two. Where hills are present, two lanes are dedicated to the uphill side; when the land is flat or gently rolling the two lane side alternates every mile or two. This means that for the single lane side you can’t pass vehicles in front of you; you have to wait until the double lane shifts to your side. Swedes are patient folk, though, so I detect no impatience among the stacked vehicles behind what is usually a semi truck pulling a large load. But even then, the semis move along at a good pace, hardly ever being seriously slowed down even by a steep hill. They just happen to move at an average pace that is slightly lower than the cars and so whenever a single lane turns double, cars passing trucks becomes the scene. The speed limit, it has to be said, is sacred: virtually nobody violates it.

I struggle to adhere to the designated speed limit because it is adjusted more subtly than most Americans are used to. In the States, there’s a tendency for speed limit to be a function of just a handful of cues (highway, back road, town, school) but in Sweden, those who have made speed limit decisions have embraced a more holistic approach. It the upcoming is not really a village but just a handful of homes in felicitious proximity to each other, the powers that be may shave 10 kilometers (6 mph) off the limit for maybe a few hundred yards and then return you to your former speed. If a stretch of highway still conforms to expectations regarding things like grade and arc of turn but presents some unexpected hazard like steep embankments or more wind than usual the highway Gods will kindly let you know that you don’t have to worry: just adopt the speed that they have in their infinite wisdom adjusted downward for you.

In short, Swedes don’t need to worry much about circumstantial adjustments to speed based on good judgment; if they just keep to the posted limits then all is right in the world. My problem is that I make semi-conscious adjustments to speed based on what I think will be expected of me rather than constantly scanning roadside for speed limit signs. I think I know what the speed limit is going to be and make my adjustment based on that, but I haven’t yet managed to achieve the finely tuned accuracy of judgment that Sweden demands. Actually, my judgment is not so bad but often kicks in a few hundred yards late: I’m slowing down but the actual sign passed a couple seconds ago and I failed to notice it.

But maybe I’m over-thinking all this speed limit stuff. The reality is that Swedish highways are fully stocked with speed monitoring cameras on posts that presumably have an automated way of issuing speeding tickets. Maybe THAT’S what I need to adjust to. Those cameras do make me nervous but they seem to only capture whatever is moving towards them and Popeye’s tag is on his tail end.

Another aspect of roads in Sweden that differs from what prevails back in the States is use of painted center lines. American highways invariably have them and they always tell you not just where the middle of the road is but also whether or not you are permitted to pass. They perform the same functions in Sweden but sometimes aren’t bothered with. Instead, the Swedes seem more preoccupied with marking painted lines that designate the two sides of the road, leaving you to your own good judgment as to where the middle of the road is and whether passing is a good idea. If it is a major highway then you can count on there being a center line as well but on lesser roads the center line is often absent.

*****

From the looks of the map and based on the sharply increasing amount of traffic on the highways, Popeye and I appear to have reached a sort of transition zone between a scantily settled Swedish north country where wilderness prevails and a more bucolic south where rural settlement is widespread and cities are both bigger and less isolated. Not big, mind you; just bigger than farther north.

After a rainy day in Gavle, Popeye and I make a short detour inland in search of a specific location on the south shore of Lake Runn. There, the plan is to pay a visit to old friends named Lance and Maria Swedish. Year after year, the three of us worked together as ski instructors at Deer Valley in Utah and although I’ve been retired from that for about a decade, they continue to be a part of the Deer Valley faithful.

For both Lance and me, the attachment to Deer Valley dates back to the winter of 1983-84 when it was in its third year of operation. Its resident skier emeritus was Stein Eriksen, its ski school employed about two dozen, and its director was a hot-headed, soft-hearted Italian American named Sal Raio. Today, the resort employs about 600 instructors so Lance and I — and not long later, Maria — were part of a process that converted a wannabe resort into one of the most elite in the world.

It was an intoxicating time to be part of something so glamorous, especially in the earliest years when everybody in the ski school knew everybody else pretty well. It makes me choke up a little just to remember it. Snow, beautiful snow floating down from a gray heaven like feathers, bluebird days when the sunlight glistened the snow, peace and solitude in a high country realm where each individual sound broke the silence, a funky old mining town just beginning to outgrow its unsophisticated roots.

Maria was Swedish from the outset but evidently decided to put a formal finish to an existing reality by marrying a man with that as a last name. Although she has made a life for herself in the American West, most of her family still lives in Sweden and so she and Lance make regular visits back to her ancestral home. When I arrive at the south end of Lake Runn, the way in is along a dirt track to a lakeside home and barn — a former farm, I suspect, that now serves as the extended family’s inheritance. And in fact, Maria’s mother — Elizabeth — still lives here alone for much of each summer, Maria’s father having died a number of years ago.

Slowly entering the unpaved driveway sends a thrill up my spine. Isolated by forest, the compound sits on a small bluff and includes the sloping land that runs down to the lakeshore and dock. An open view, there is, out across the lake to splendid, rolling countryside of forest, farms, and meadows on the far side. The lake is complicated with many bays and inlets which means a view across it keeps the opposite side close enough to readily discern the details of human activity and even the individual trees in the forested areas.

All of which stabs me with a sudden reminder of the idyllic setting of my childhood growing up next to Newfound Lake in New Hampshire. I have lived a charmed life, but no part of it has been more charmed than the childhood years next to that lake. It is as if this outlook across Lake Runn were designed to say, “This is what becoming an adult has cost you.”

There is Lance walking out the driveway to meet me. He and I have never gotten together to do things — never even gone off for a few hours to ski together — and yet, at least from my point of view, we ought to have been ‘comrades in arms:’ there is a mysteriously deep level of trust between the two of us that is obvious every time we happen to meet.

Lance was still a teenager when he arrived at Deer Valley, out on his own, starting adult life as a ski instructor far from his childhood home in Wisconsin. From the very first meeting, I sensed that he was mature beyond his years, reliable and sensible, hard to anger, hard to rattle — and yet relaxed and open.

Lance introduces me to the extended family of which he is now a part. He and Maria make sure nobody is missed, irrespective of age, and the level of socialization that ensues thereafter surpasses anything I’ve known for years.

Because a morning work project used bribery to get the kids and teenagers to participate, in mid-afternoon we all made an excursion to a nearby ice cream shop next to a canal connected to Lake Runn. Even it conjures memories; when I was young my parents and I used to get together with a few friends and drive down to the far end of the Newfound Lake where Millstream Ice Cream located next to a small brook would let us choose our flavor. In those days, the choice was three, not 30 or more.

There at the ice cream stand, we part company. They return to their Lake Runn getaway, but before going my separate way, I walk across the street and take a look at the ancient church in which Lance and Maria were married.