In southern Colombia, not far from Ecuador, there is monument to something that people don’t believe in nowadays: a miracle. It is a basilica church called the Las Lajas Sanctuary. The Spanish word “lajas” translates as “rock slabs.”

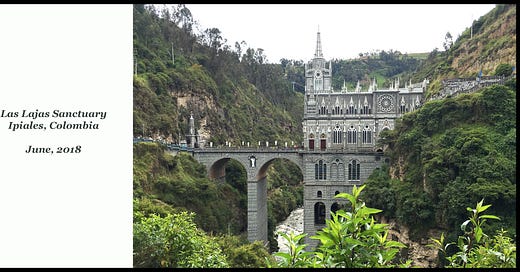

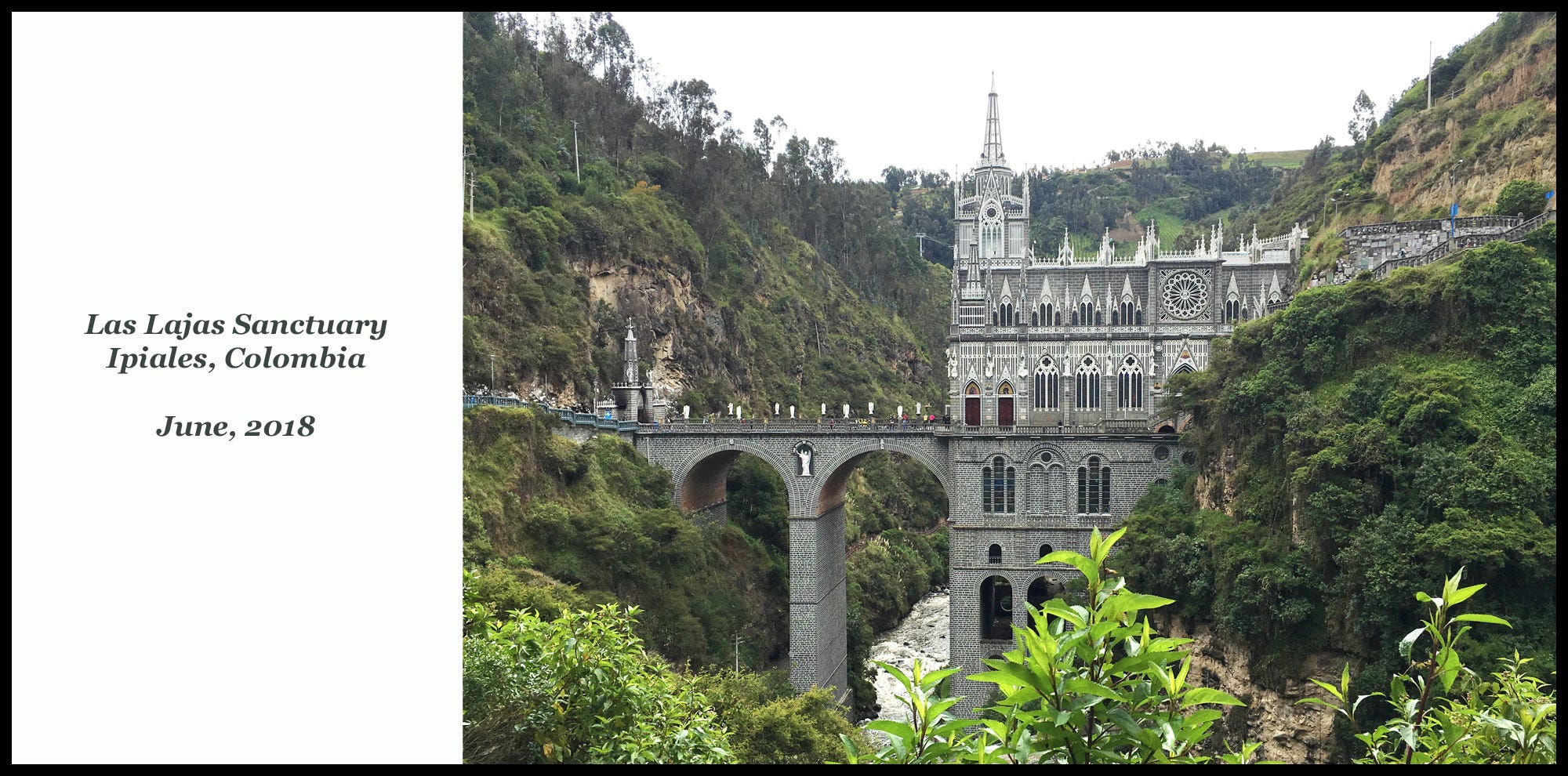

Constructed in the first half of the 20th century, it is a Gothic-style treasure situated near the bottom of a deep ravine that plummets hundreds of feet down to a fast-flowing river. So steep is the land on which the church has been erected that its foundational “basement” extends downward as much as the church itself ascends upward. The entry to the church faces the river, but is greatly elevated above it. A bridge across the gorge acts as a sort of plaza a little lower than the church portal. The bridge and the church are designed to be a single construct.

The arched massiveness of the bridge appears to be a natural extension of the church foundation. The top surface of the bridge is a horizontal plane below which everything is solid and simple whereas everything above is elegant intricacy. It sounds like a formula for disaster but when you view the whole from an upstream vantage in the canyon that one can easily walk to, it looks right.

The inspiration for Las Lajas is a miracle that occurred in the 18th century.

You will have noticed the wording used to make this assertion: “. . . the miracle that occurred . . .” and not “. . . the miracle that is alleged to have occurred . . .” or “. . . the miracle that is reported to have occurred . . .” This will leave you with the impression that I believe in miracles. That is because I do.

The modern, secular world rejects out of hand the possibility of miracles and for many years I was a card-carrying member of the modern world. But a funny thing happens as you get older: you actually become more open-minded regarding socially unacceptable notions. Anyway, here’s an article that describes the Las Lajas miracle:

“Painted by Angels” . . . Colombia’s Miracle Portrait of Virgin & Child

By Paul Likoudis

(In this article Paul Likoudis takes a closer look at the miracle of Las Lajas, near the border of Colombia and Ecuador, and the incredible portrait of Our Lady and Child "painted by angels" on the rock. The most amazing fact is that the image is not painted at all — the colors of the portrait are the actual colors of the rock itself!)

***

. . . on the border between Colombia and Ecuador, is another of South America's most important Marian shrines, though it is largely hidden in a steep canyon above the Guaitara River. The Sanctuary of Our Lady of Las Lajas in Ipiales is the fourth structure built on the site since a miraculous portrait of Our Lady and Child was discovered in a cave in the middle of the 1700s by an Indian woman carrying her deaf-mute daughter.

The Gothic-style church is considered one of the architectural wonders of the world, and according to the testimonials that line the walkways leading to the church, Las Lajas is rich in miraculous cures.

Most miraculous of all, however, is the portrait of Our Lady and Child, along with St. Francis and St. Dominic, which appears to be painted on rock. But German scientists, after boring through various parts of the "painting," discovered that the rich surface colors are not paint, but are the actual colors of the rock, which run several feet deep. Indeed, no one has ever come up with an explanation for the phenomenal painting.

According to tradition, one day in 1754, Maria Mueses de Quinones, an Indian woman from the village of Potosi, Colombia, was walking the six miles between her village and the neighboring one of Ipiales, carrying her eight-year-old deaf-mute daughter, Rosa. As she approached a place called Las Lajas (the Rock Slabs), which was widely rumored to be haunted, she paused to rest. Her daughter got off her back and ran into the cave to play. A moment later, Rosa came running back, exclaiming, "Mummy, there is a woman in here with a boy in her arms!"

Maria was shocked; this was the first time she had ever heard her daughter speak. She grabbed the child and hastened on to Ipiales.

Now, according to an account by the founder of Tradition, Family & Property, the Brazilian Dr. Plinio Carrera de Oliveira, Maria's friends and neighbors refused to believe what she had reportedly seen. Then:

"A few days later the child Rosa disappeared from home. After looking everywhere the anguished Maria guessed it: Her daughter must have gone to the cave. She often said that the woman was calling her. Maria ran to Las Lajas to find her daughter kneeling in front of a splendid woman and playing affectionately with a Child who had come down from His Mother's arms to let the girl enjoy His divine tenderness. Maria fell to her knees before this beautiful spectacle; she had seen the Blessed Virgin.

"Fearful of ridicule, Maria kept quiet about the event. But frequently she and Rosa went to the cave to place wild flowers and candles in the cracks of the rocks. The months went by, with Maria and Rosa keeping their secret. Until one day the girl fell gravely ill and died. A distraught Maria decided to take her daughter's body to the Lajas to ask the Lady to restore Rosa to life.

"Pressed by the sadness of Maria's unrelenting supplications, the Blessed Virgin obtained Rosa's resurrection from her Divine Son. Overflowing with joy, Maria went home. It didn't take long for a crowd to gather. Early next morning everyone when (sic, went?) to Las Lajas, each wanting to check the details for themselves.

"That was when the marvelous picture of Our Lady on the wall of the grotto was discovered. Maria Mueses de Quinones could not recall noticing it until then.

"The Child Jesus is in our Lady's arms. On one side of our Lady is St. Francis; on the other is St. Dominic. Her delicate and regal features are those of a Latin American, perhaps an Indian. Her abundant black hair covers her like a mantle (the two-dimensional crown is metal and was added by devotees much later on). Her eyes sparkle with a pure and friendly joy. She looks about 14 years old. The Indians had no doubt: This was their queen . . .

"But who put this magnificent image there? The author has never been identified! Scoffers say the wily Dominicans sneaked in a good artist, and the gullible Indians are still being fooled. But tests done when the church was built show how stupendous this image actually is.

"Geologists from Germany bored core samples from several spots in the image. There is no paint, no dye, nor any other pigment on the surface of the rock. The colors are the colors of the rock itself. Even more incredible, the rock is perfectly colored to a depth of several feet!"

Las Lajas was built to commemorate this miracle.

Inexplicable things happen often and anything that science can’t rationally explain has the potential to be cast as a miracle. But then, a great many scientists will dismiss any miracle on the grounds that it is impossible. Their reaction is mere speculation grounded in the unscientific belief that science will eventually uncover an explanation of the phenomenon — an explanation based on predictable processes that operate in this world.

Impossibility alone does not get us to a miracle. It is a necessary ingredient but not a sufficient one. A miracle requires that the impossible thing be intentionally wrought. Some sort of intelligent force has to be behind an impossible happening before we can begin to think of it as miraculous.

Intelligent force! Intelligent force! Am I talking religion here? Well, no, not directly, but wouldn’t you agree that it is hard for something to be a miracle if it doesn’t flaunt science? How might an impossible event occur without undermining the scientific presumption that the world behaves according to predictable natural laws. Anything deemed impossible logically contradicts some widely accepted scientific law. The science establishment gets put on its heels and resents the challenge to its authority.

Science cannot be the arbiter of what is or is not a miracle because it is biased: it believes as a matter of principle that miracles are impossible. Contemporary science is constructed on a belief system that does not recognize any explanation of worldly phenomena if its cause is posited to be something that cannot be measured or detected. But this is self-defeating, is it not? Science progresses by observing phenomena that are at present unexplained, and then hypothesizing the existence of either a new force or a new concatenation of known forces and testing to see if the hypothesis can be proved invalid. Science does not validate the new hypothesis; it progresses by demonstrating the failure of multiple efforts to invalidate it.

This means that supposed proof of a scientific law is nothing more than the failure of many well-designed experiments to invalidate the original hypothesis — and this in turn means that a physical law actually amounts to belief rather than conclusive proof. There is nothing wrong with this; it is belief based on strong circumstantial evidence and it is the best that can be done since there is no way of checking every single instance in which a theorized cause leads to a predicted outcome.

In a certain sense, science itself is a miracle since the only good science is science that people can believe in. Science abhors belief as a hindrance to objective investigation and yet the aim of science is to discover/construct explanations that can be believed.

Science advances by allowing skepticism to challenge its established principles. And yet, the more efficacious a particular scientific theory becomes, the greater the likelihood that skepticism is being displaced by belief — and belief is always the dragon that must be slayed for science to progress. Without skepticism science is dead.

But back to the exact status of miracles. The main reason contemporary secularists dismiss miracles out of hand is that their minds have no tolerance for the existence of a knowledge realm lying beyond the human ken. Only those who are capable of humility can afford to have that sort of tolerance. Secularism is loathe to admit that there is anything at all that the human mind cannot eventually penetrate — and this encourages arrogance.

A realm exists in which the methods and principles of science are not useful. The modern bias is to view the accomplishments of science as evidence that the non-science realm has been surrounded, is being constricted, and is destined to collapse.

But in fact the non-science realm is the more important (and even more pervasive) one since all human value judgments are made within its space. Humans being human, pure science tends to occur only as long as its practitioner seeks truth in deep obscurity. As soon as the work of the scientist receives public attention, the self-interested human is tempted in countless ways to pander to the love and lucre that the discovery might garner. The degree to which this occurs depends on the moral character of the hero, but the overall consequence is corruption.

In pure science, nothing would be more intriguing to the scientific investigator than a miracle. Any event that defies current knowledge and understanding, and gives the appearance of having been intentional, is innately fascinating. Here is something that obviously defies established laws in science. Even though science knows that all its laws are subject to modification or displacement with time, human nature is reluctant to abandon the security of a socially accepted explanation of the world view that science has shaped.

Once science became rich and famous, scientists became conflicted between the obvious intellectual excitement of solving a miracle and the discouraging realization that a good solution will yield little in the way of a worldly reward. In an all-to-human manner, the typical reaction is to dismiss the miracle as a triviality that will get sorted out at some future time.

There may be good reason to reject any one particular miracle but to reject miracles in general is a form of prejudice. What evidence is there to support the belief that miracles must succumb eventually to the savagery of science or else be dismissed as hoaxes foisted on the credulous? What right does the scientist have to reject something based on nothing more than belief?

Besides, scientists have no problem with a miracle if it advances the reputation of the field. Why, for example, do secular scientists find it so easy to accept as reasonable that the entire universe involved a big bang originating from an infinitely small point — too small to reasonably expect that we might ever be able to observe or measure it? (How big is a piece of matter that is infinitely small?). Would it not be more sensible to admit that the coming into existence of matter is a miracle? Something issuing out of nothing seems miraculous to me and particularly considering that any notions of random chance “causing” it seem absurd.