It is one thing to be of two minds about something, but what does it mean when the conflict is between two emotions. On the one hand, I am looking forward to today’s visit to Versailles but on the other, I resent that I ‘have to go there.’ Well, we’re on our way so I guess the one hand won out.

We’re definitely in the danger zone that surrounds the chaos of movement and sound that prevail in a big city, but we’re coping, we’re coping. With a little help from English speaking pedestrians, we find the parking lot without much trouble, and by observing the behavior of others I grow comfortable with circumventing the lot’s paid parking barrier and leaving Popeye right beside the entry gate for the palace.

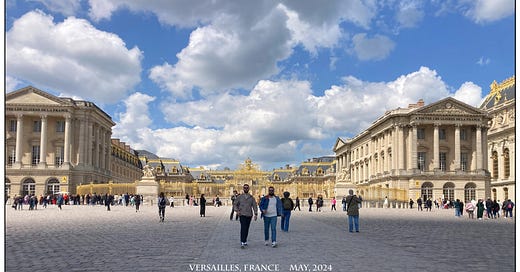

But the word ‘gate’ -- although technically correct -- is far different from what a reader might conjure in the mind’s eye. Ordinary words cannot describe the opulence and ostentatiousness that surrounds what is functionally nothing more than a simple barrier to entry. But the barrier is open and the masses are milling their way into and out of the grand estate.

But wait; this is not the entry. It is the entry to the entry. This is just an exterior courtyard, wider than a football field and longer than two of them. On all three sides are multi-storied wings of the palace that completely embrace the courtyard. Entry into the palace itself is another matter, as is freedom to roam in the stupendous gardens that extend virtually endlessly on the back side of the palace.

I find the small room that the public may enter without a proper ticket and there a supercilious Frenchman deigns to answer my questions. We have trouble understanding each other, a feeling that is sincere on my part. I think he must hate Americans. But in the end I do learn from him. Tickets MUST be purchased online. If I were in a position to buy a ticket online, the first available time slot is 3.5 hours from now. If I buy that ticket, it only allows me entry at that designated time if I am far enough advanced in the waiting line to be part of the allowed quota; farther back in the waiting line and I will have to wait for the next time slot for which peasants are permitted a look-see. Once this Frenchman and I are done with each other we say our goodbyes with exaggerated friendliness.

I step outside and stand at the top of the short stairway leading to the small room. From here, I can survey the waiting line that runs the full length of the courtyard. This is when I triumphantly conclude that I’m above all this. There’s no need for me to see King Luis’s knick-knacks. There’s no reason why this human soul, already almost a century out of date, should be so not-so-subtly humbled. With a feeling that I am doing the right thing, I decide to turn my back on the wonder of wonders, the greatest of all palaces, the envy of the world, and go eat lunch.

I feel no regret. I even dismiss out of hand the idea that I may return at some later date. This idea of returning ‘next year, of maybe the year after’ is an illusion that I often allow myself whenever a chance is missed to see a special place or have a special experience for the first time in my life. I really do use this illusion, even while knowing that I am lying to myself, and it quenches feelings of regret. But now here with Versailles I have become so alienated that such absurd behavior isn’t required. Not seeing Versailles has become one of my accomplishments in life.

Popeye and I leave both the palace and the town of Versailles in search of the place where we expect to spend the night: at the Centre Port Royal in a little forest outside the small village of Saint-Lambert. It is less than half an hour drive to get there and as we approach the end of the trip Sygic misdirects us.

We turn right on a little narrow road that in North America would be evidence in its own right that we’re on the wrong track but in much of the rest of the world could very well be the correct route. Almost immediately, we encounter a middle-aged French woman -- lithe, dynamic, and bursting with energy -- who is in the center of the road ‘manhandling’ two large, plastic rubbish bins. I stop (indeed, have to stop) and ask her the way to the Port Royal Hotel. She knows less English than I know French so we ramp up the non-verbal cues in an effort to communicate. Eventually, she recognizes that what I have called the Port Royal Hotel is commonly known as the Centre Port Royal, and manages to give me hand-depicted directions to its nearby location. All the while, she is virtually laughing at the absurdity of the situation and betraying her inability to be anything other than a lover of life. If I were to be around her much longer, I’d be falling in love with her.

Centre Port Royal, it turns out, is a retreat in the middle of a forest -- a rare thing this close to a big city. It is a place where people get married or groups have little get-togethers for forest hikes or peaceful interludes. But it rents rooms for the night and also serves meals. My room has a large window that looks into the forest, thick with trees and containing enough undergrowth to make it real but not so much as to obscure its arboreal character. I sleep deep in such a place; I’ll no longer think of it as a hotel.

After a restful night, Popeye and I skirt the southern edge of Paris and head east. We’re using high speed ring roads to do this and the process lasts longer than I would like -- but then, I wouldn’t be happy with it lasting at all. We make it, though, and eventually leave all the busy-ness behind.

At first, the surrounding rural land is a flat plain but then gradually the terrain begins to heave and roll in an almost imperceptible manner. Surprising it is how little elevational change is necessary to make something ordinary begin to seem special. This is open farmland fields with hardly a trace of forest. The acreages are vast, like you might see in Middle America, but the geometry imprinted on the landscape is less repetitive. Prosperous it is, and well-tended. Farming in this part of France appears to be on a grander scale than what we saw coming up from the south. Everywhere we have been the farms have looked well-kept and robust, but only here do farm sizes begin to approach North American norms when it comes to scale.

By the end of the day we are checked in at a hotel on the outskirts of Riems, a city well to the east of Paris and not far from the border with Belgium. A few days ago, on the phone with Michelle, I was carrying on about how big city traffic bothers me and she asked why I don’t just park myself at some hotel on the edge of town and take public transit to the city center. It is a manner of thinking that is alien to an American of my generation, but of course for European cities especially it is an eminently practical suggestion. This lodge on the edge of Riems sits side-by-side with the terminal stop of a regularly running light rail system, so I give Michelle’s approach a try.

Riems is not a large city but even so it has a light rail system. Actually, it is not light rail but I don’t know what to call it. It walks like a duck and quacks like a duck but it doesn’t run on rails. It’s a three-car train that runs on rubber wheels and follows wheel tracks in the road base that are distinguished by a differently colored substance that is flush with the road base itself. The three-car train appears to be capable of complete independence but in fact slavishly follows its designated track and -- just like light rail -- only stops at designated stations that consist of small, slightly elevated platforms. A pedestrian can easily step up onto one of these platforms and at the same time it is just the right height for stepping into the three-car train.

Meanwhile, the city traffic of both vehicles and pedestrians is free to roam. They can use the street at will, but recognize that the tracks in the road receive the same sort of alert respect that the tracks of a real train signal to anyone wishing to cross them. I find all this most intriguing, but when I go to try the system a three-car train arrives at the same time and I do not have time to figure out the payment system. On, shoot, I’ll just board anyway; maybe one pays inside and if not then I can always plead ignorance.

As soon as we are on our way to town, I ask two people if they can help me in English, but neither one can. Then I notice a diminutive Asian gal, probably in her twenties but with skin so alabaster smooth that she looks like a minor. She wears big-lense glasses that have thin, black frames and she looks approachable. I turn to her and ask if she can help me in English. Yes, she can, and yes, she knows the payment system: you do it at a little device mounted on pole at the edge of the platform.

This young lady, I learn, is a university student from China, here to study . . . French, of course. She asks me where I’m from and what I’m doing here in Riems. When I tell her that I’m on a motorcycle trip, headed for Norway, her mouth drops open and she asks if I’m traveling alone. When I tell her yes her Asian eyes become surprisingly large and she gives me a thumbs up. She likes my project, it seems, but the train slows to a stop and it is time for her to disembark.

Her reaction was very encouraging. She obviously approved of what I’m doing and this I take as a sign that my wanderlust is not simply a function of some sort of minority glitch in Western culture. If even a Chinese woman approves, I’m convinced this has to be a recessive gene of some sort.

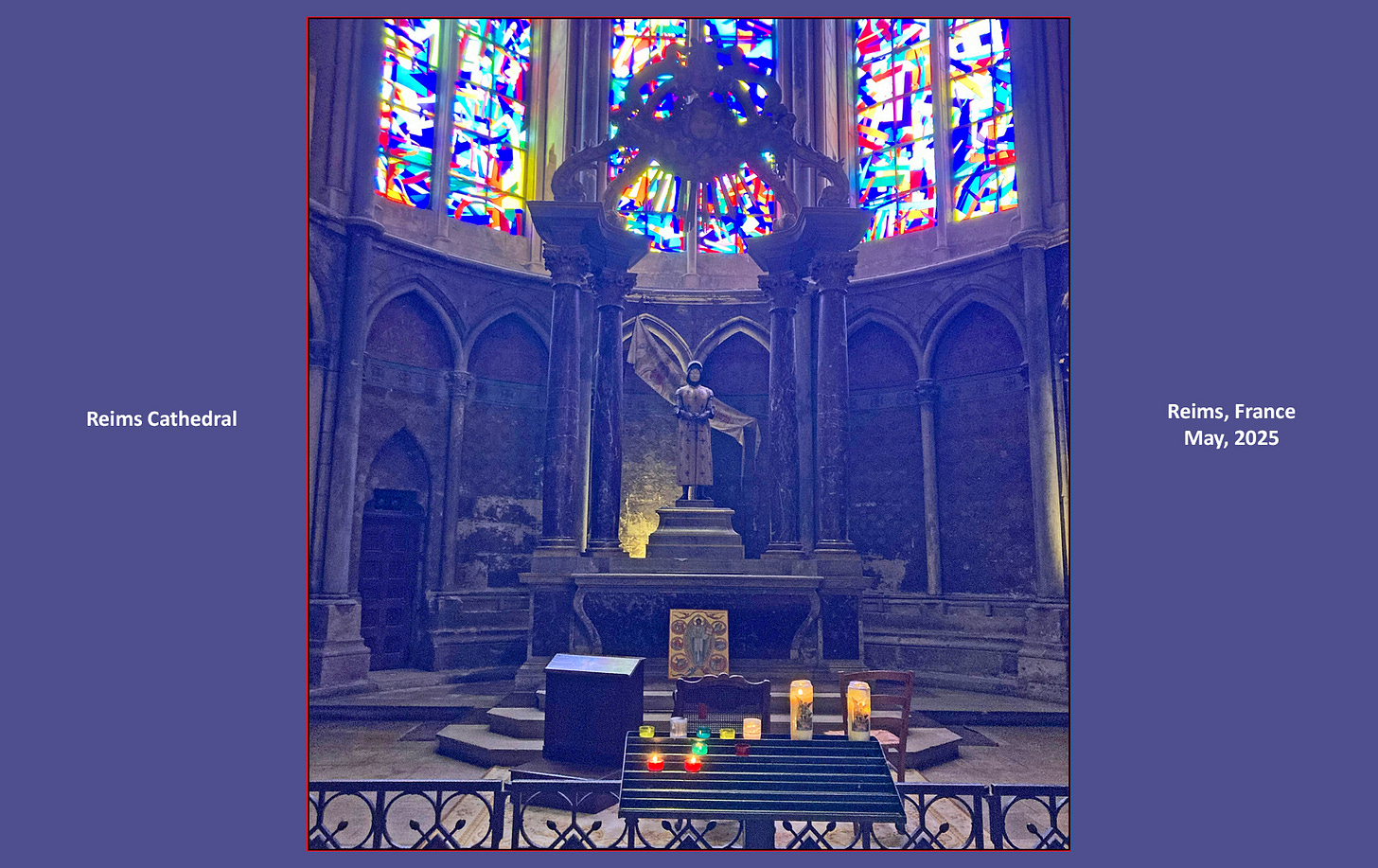

The trip to town in Riems is unremarkable. I walk the streets, eat some third rate Chinese food, and stumble across the city cathedral -- as big and complex as most but in a more degraded condition than usual. Nonetheless, I do the obligatory walk-through.

On the 8th of May, Popeye and I head north across the border into Belgium. This I view as the fulfillment of an intermediate goal designed to keep us on track with the goal of arriving at the top of Norway by the end of June. We hope to reach the Baltic coast of Germany by the 20th of the month and then get to Oslo by its end. That will leave the month of June for exploring the Norwegian coast. There are many diehard motorcyclists who, because of constraints on their free time, do a similar outing in two weeks instead of two months.

We are now in the southeastern corner of Belgium, a surprising region that has a level of ruggedness and wildness that conflicts with the image of the ‘Low Countries’ that many people have in their mind. Decades ago, parents and grand parents might have been able to teach the younger ones that this area is different, but the survivors of World War II are now almost all dead and there is nobody around to narrate first-hand experience with the Battle of the Bulge, the Seige of Bastogne, and the horrors of the Ardenne.

The Ardenne is forest country -- mostly evergreens. The terrain appears to be a sort of plateau, only recognizable because here and there a back road forces you to drop hundreds of feet down into a steeply sloped gulch and then work your way up its other side. And all of this with thick forest that keeps you blind as to where you are and where you’re going.

There are towns but the region lacks even small sized cities. There are farms and open fields, but they appear sporadically and almost always look as if they have been granted exceptions by mother nature. Perhaps I overstate it a bit, but that is because I am surprised by the semi-wild character of this region. Back across the border in France the landscape was virtually forest free, cultivated and prettified to the nth degree.

On a more superficial level, it is interesting to note certain roadside idiosyncrasies that seem to be nation specific. In France, for example, every village no matter how small would have a standardized form of road sign giving its name, but Popeye and I would occasionally pass through some little town that had its sign mounted upside down. I later learned that this is form of protest against national government policies that rural folk think willfully disadvantage them.

Here in Belgium, I discover that whenever there is an upcoming sign that will lower the legal speed limit, there is a duplicate sign in advance that is posted with the added message below that reads “300 M(eters). If you don’t slow down in time, you’ve been forewarned and have no excuse. Another road sign curiosity I have yet to see elsewhere is a simple one on which is written the single word, “Aquaplaning,” a sort of equivalent, I suppose to “Slippery when Wet.”

Many of the villages in this neck of the woods have a reputation for being picturesque, and we end up in one of them. It goes by the name of Dinant, an occupant of one of the aforementioned gulches. It lines the two sides of the Meuse River with timber frame homes and stylish old buildings, all dominated by a very unusual church that has the onion-shaped steeple of an orthodox type. Behind the church is a near cliff on the top of which is a concrete fort that can be reached by a short funicular that departs from nearby.

Dinant was the furthermost extent of the bulge that the German army created when it tried to break through the allied lines in the dreadful winter of 1944-45. It also happens that Dinant was a place of action in World War I, something that resulted in a statue of Charles De Gaulle being erected next to the bridge over the river which for all practical purposes is the center of town. “Why should a Belgian town honor a Frenchman?” you may ask. As it happens, De Gaulle was a lowly infantryman who was part of a small French contingent sent to defend Dinant against the invading German army. He did nothing of note in Dinant and in fact the French force defending the town suffered only one casualty, the death of an individual soldier killed by a sniper. De Gaulle obviously wasn’t even the victim of that event. I suppose that once a person has a certain level of recognition and fame, more of the same comes his way without even doing anything. But at least the statue is an artistic success: it evokes the man without even giving him a recognizable face.

After taking coffee and wandering around town, Popeye and I track down the tiny rural village of Gedinne and spend a couple nights in a small country inn called Le Relais du Moulin. Owned and operated by a matron named Anne who appears to do all the work, the inn is the perfect getaway for anyone seeking relief from the pressures of modern life. Not only is the lodge homey and comfortable, not only is the surrounding countryside unpretentiously charming, the proprietor Anne has found her calling. She meets me at the door, helps me put Popeye to bed, makes me gourmet meals, and presumably cleans up after me when I leave. And all of this is done with a beaming smile on her face -- not a fake, please-the-customer smile but the smile that naturally comes to the face of someone who believes in what they do and believes it has been done right.

During the layover day, Popeye and I take a trip to a couple other Ardenne villages known for their kerb appeal: la Roche en Ardenne and Durbuy. The latter is a lovely town that has succumbed to the lures of the tourist trade, but la Roche en Ardenne is a different breed of cat. In World War II, the town was almost entirely destroyed and a very large number of its inhabitants were killed. La Roche is considered to be the Belgian town that suffered the most devastation during the war.

How it all came about is a sorry tale. During the Battle of the Bulge, the German offensive was advancing inexorably and the American troops trying to stem the advance were overwhelmed and had to retreat. It happened so quickly that the Americans had no time to destroy a critical bridge in town. Following the retreat, American artillery from behind the lines had to do the job and in those days shelling from big guns was not able to achieve pinpoint accuracy. In the process of hammering the bridge, the guns hammered the town as well. In the larger scheme of things, the American action helped blunt the German advance, but as always happens in war the collateral damage went ballistic -- and friendly fire cannot distinguish between soldiers and civilians. (Question: Which was worse, la Roche en Ardenne or Monte Cassino?)

When the time comes to depart from le Relais du Moulin, Popeye and I head for Bastogne, the focus of a struggle by an American army completely surrounded by the German advance to hold out until reinforcements might come to their aid. In this instance, it was the Alamo with a happy ending. They succeeded in repulsing many German attacks over many days until General Patton, the flawed hero of American land forces, drove his army a miraculous distance north to break through to Bastogne. American survivors of the seige insist they could have held out for however long was needed but this warrior spirit in no way diminishes what Patton did.

In the town of Bastogne, I get tied up in a Gordian traffic jam that takes an hour or so to sort itself out. By the time Popeye and I reach the far side of town where the museum in honor of the event is located, time is so short and crowds are so big that I elect to forsake the intended visit and instead make a slow-paced, peaceable passage on back roads across the tiny country of Luxembourg to a little town just across the far border into Germany.

Luxembourg is a country I have never really visited before. I say “really” because I have a vague and perhaps incorrect memory of having passed through it on public transit decades ago. If I don’t remember it, did it happen? This time, though, it leaves an impression. Luxembourg city down south -- we don’t go there. Instead, we’re in the countryside patching together the little roads that connect one small village to the next. But here’s the thing: this countryside jaunt quickly establishes that the country is obscenely rich. Works in project are rare. Not everything looks new, of course, but even old things look as if modern methods have made them just like new. The roads we are on are silky smooth. Hardly ever is there any sign of roughness or degradation; never is there an indication of a patched pothole. It is as if the whole road network was paved just last week. Cars, trucks, and farm machinery all look as if they’ve yet to be initiated into the real world.

Then there’s the countryside, a landscape that is manicured to within an inch of its life. Trees planted roadside are regularly spaced and all at the same level of maturity. Meadows in which livestock graze have grass so perfectly clipped that you’d think the cows must be trained barbers. Trees and forests (yes, they do exist, although cleared land is much more extensive than back in Belgium) are either stands of deciduous or stands of coniferous -- never both and always defined by straight line borders. Everything -- but everything -- is worked over so totally that it feels as if every species of plant has been totally domesticated and only occupies locations chosen by man, only continues to exist as long as it retains the right confirmation. If there is a place in this world in which man actually controls nature rather than the other way around, it may be Luxembourg.

I like to call it Lollypop Land because there is a favored deciduous tree that appears to grow to a finely toleranced size and has an orb of branches and leaves that so closely resemble a ball on a stick that it reminds me of a giant sucker. Aah, but first impressions are often highly misleading so if you are wise you will dismiss most anything I say about Luxembourg.

It doesn’t take long to pass through -- less than an hour, I’d say. We cross the border into Germany and find our way to the little town of Zemmer where a zimmer awaits. The lodge keepers are a meaty, middle-aged couple who might consider a different kind of work. Let me be clear: they are efficient and responsive and they say all the right things, but their heart doesn’t seem to be in it. I don’t mean to fault them; we all have to make our compromises and in a formal or technical sense they are fulfilling their roles in life admirably well. I think maybe I’ve been spoiled by having spent the preceding couple nights at Anne’s le Relais du Moulin.

Well, here we are in Germany where just about everything is taken seriously. Popeye and I have picked up an autobahn heading east and for sure the motorists are serious. They don’t honk, they don’t bicker, and they play by the rules -- all the rules. Traffic moves along at a terrific pace, perhaps because everybody is so focused on doing things right. We’re headed for the twin cities of Mainz and Wiesbaden next to the Rhine so traffic becomes heavier the farther we go. Just past those two modestly sized cities lurks Frankfurt, a more imposing metropolis, so Popeye and I are doing our best to be good little Germans since we’re surrounded by a buzzing swarm of busy bees pushing the speed limit. We’re as motivated by survival as we are by social pressure.

Our stop for the night is at a hotel/hostel in downtown Wiesbaden. It is called a hotel on Booking.com but has a door plaque that refers to itself as a hostel. The confusion is understandable; the place has attributes typical of both. On the one hand, the rooms are like hotel rooms that have private bathrooms; on the other, there is a kitchen and dining room with everything required for cooking and eating. I get the feeling that some people are living here on a permanent basis. Anyway, it’s a good deal; the price is right and the center of the city is a five minute walk away.